FORT WORTH, Texas — Opal Lee had a simple rule in her home. If her kids were reading a book, they didn’t have to clean.

“I didn’t disturb them,” Lee said. “I’d rather they read than the house was clean.”

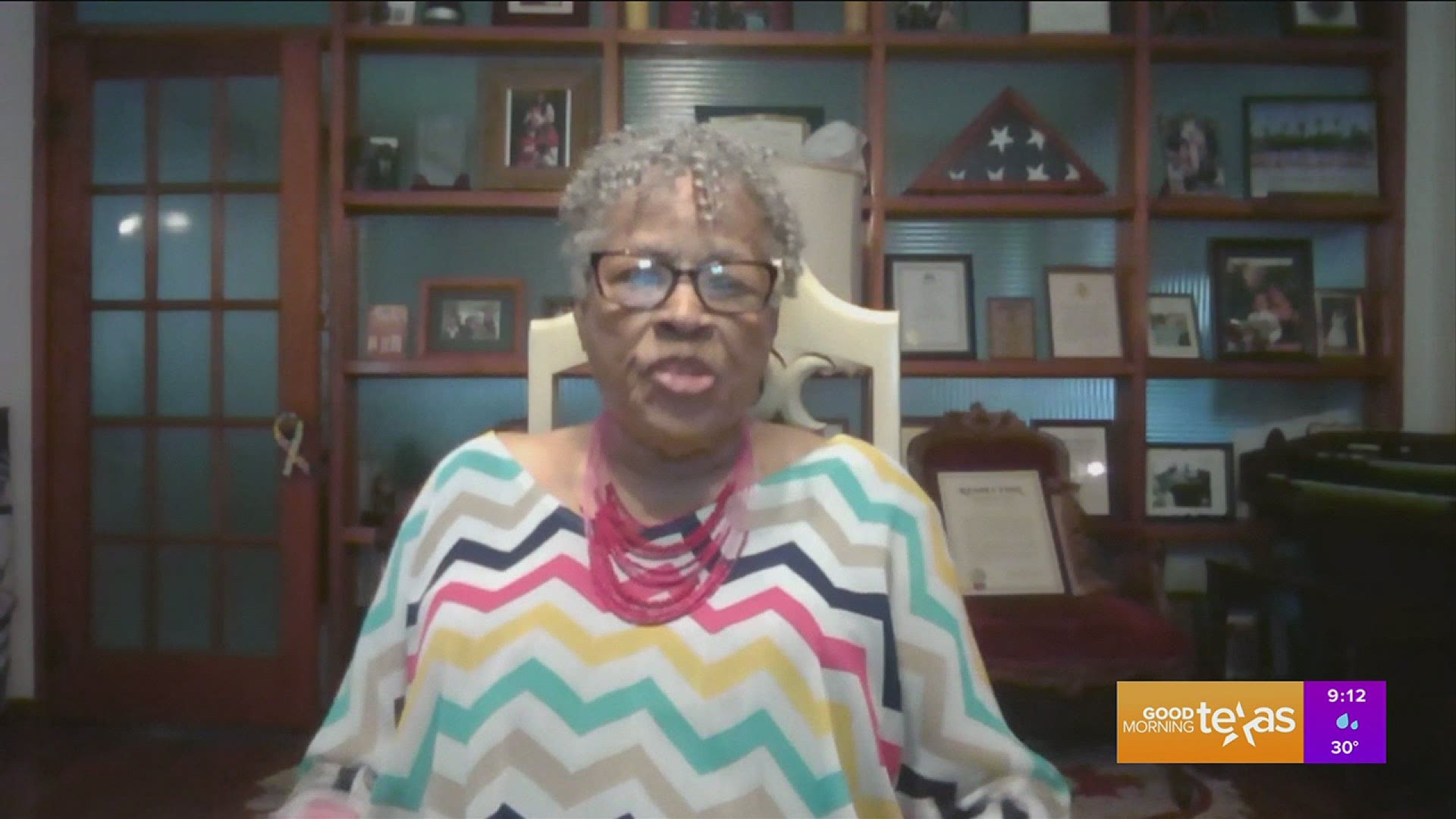

Now, the 94-year-old’s home doubles as a museum to her life’s remarkable story and a large, organized library, which you’d expect from the former educator who hasn’t stopped trying to teach.

Lee, known to many as “Miss Opal,” is deeply involved and rooted in the United Riverside neighborhood.

Her granddaughter, Dione Sims, helps Lee with her still busy daily schedule and with managing Opal’s Farm, which is new but could eventually expand to 13 acres of Trinity River Water District land right along the river’s edge. Last year, it provided 7,700 pounds of discounted food.

“At the end of the day, her greatest concern is the welfare of the human being,” said Sims.

The idea came from Opal’s years working for a local food bank, along with the 15 years as a Fort Worth ISD teacher and 10 as a counselor for the district.

“I taught children who would come to school hungry and they couldn't learn,” Lee said. "I saw firsthand what it was doing.”

Sims’s other focus is tracking the signatures on Miss Opal’s Change.org petition to make Juneteenth a national holiday.

“She just got this bee in her bonnet that said, ‘I want people to be aware,'” said Sims.

Opal Lee is likely best known for her decade-long effort to make Juneteenth a national holiday. She’s on the board of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation, and her online petition now has a goal of 3 million signatures.

“I just haven't given up,” Lee said. “I just know it's about that time now that we're going to have Juneteenth, a national holiday.”

In her younger years, Lee helped organize the city’s Juneteenth celebration and used it as a fundraiser for local nonprofits.

“I'm passionate about having Juneteenth a national holiday, and I feel Juneteenth is a unifier,” Lee said. “I'm wanting us to unite so that we can address the disparities that are happening to us now.”

Juneteenth is state holiday in Texas and 47 other states, but Texas also recognizes Confederate Heroes Day as a state holiday.

Even in her 90’s, Lee has continued to walk two and a half miles every year marking the two and a half years, between the emancipation proclamation and when Union Major General Gordon Granger brought the news of freedom to the shores of Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865.

“None of us are free until we are all free,” said Lee.

She first celebrated the holiday as a kid in Marshall, Texas before moving to Fort Worth at age 10.

“Her mother sold the cow for train fare so they could move to Fort Worth,” Bud Kennedy, a columnist for the Fort Worth Star Telegram said. “That sounds like something that you would hear out a storybook.”

Kennedy has covered Opal’s movement from Fort Worth to Washington D.C.

“She just always been working on things that help the community. She taught so many kids and help you know, raised so many kids through her through her schoolwork,” he said. “She's become this local civil rights figure who became a national civil rights figure.”

There’s one story, though, Opal kept mostly secret her whole life, even to some close to her.

“We did not grow up hearing about what happened in 1939,” said Sims.

“She never told us what had happened, and people seem to know about it, but it wasn't until last year that I saw her come out and make a speech and talk about the time that her family was attacked,” said Kennedy.

Lee’s family moved into a home at the corner of New York Avenue and East Annie Street.

“It was a neat little place and my mom had it fixed up so nice,” Lee said. “Two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen.”

But they were a Black family in a white neighborhood.

“The people in the neighborhood start gathering,” Lee said. “There were 500 strong.”

“The mob came, throwing bricks and bottles,” Kennedy said, describing newspapers clippings from Fort Worth and wire services.

Standing at the intersection, Lee can point to where she headed to stay with friends and describes her parents leaving under the cover of darkness.

“The people tore the place up. They burned furniture. They did awful things,” Lee said. “My dad who was at work, came home with a shotgun and the police told him if he busted a cap that they let the mob have them.”

Fourteen police units at the home did nothing to stop it, according to newspaper stories of the attack.

“The wire service stories carried outside Fort Worth, the coverage was, you know, extremely vivid, ‘Fort Worth family attacked by white mob’,” Kennedy said. “You didn't see those headlines in Fort Worth.”

The day of the attack was June 19, 1939. It was Juneteenth.

“If we had an opportunity to show them what neighbors could be like, that wouldn't have happened,” said Lee.

Today, the corner lot is as forgotten as the story that happened there. It’s vacant and covered by fallen branches and trash tossed on it.

“It wasn't something that held a bitterness for her,” Sims said. ”It wasn't something that fueled her to hate white people.”

“She wants to be openly the teacher and the leader, and you know she really does not play the martyr,” Kennedy said. “She doesn't go out and lead with and say, ‘You know my family was the victim of a mob. Would you help me with this?'”

In the decades since, the push for civil rights happened much more quietly in Fort Worth than in Dallas.

“What sticks out to me is that Fort Worth was not a city where you saw demonstrations of any kind,” said Lee.

Sarah Walker, 83, is the vice president of the Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society.

“There was no need for any confrontation or any upsets through communities and neighborhoods and families and friends,” Walker said. “When the migration came about and Blacks started moving into other neighborhoods, then the white folks started moving out.”

Walker said the story of Black history in Fort Worth has gone overlooked for years.

“I like to tell people the most that this city belongs to all of us. No one has a right to try to decide who's going to live here. Who's going to live here. Who's going to work here,” Walker said. “I don't know that we realize who we are. And what contributions we made to this country.”

As Fort Worth quietly changed over the years, it wasn’t until 2020 that Miss Opal’s lifelong efforts towards promoting Juneteenth and equality and reached the rest of the country.

“Everything about Opal is this wonderful Fort Worth story that we took way too long to tell people about,” said Kennedy.

The killings of Black Americans across the country led to protests that opened eyes and minds to how close the past is to the present.

“Those kinds of things are wake up calls, and people have decided we're not going to take this anymore,” Lee said. “This has made people aware that we've got to do something different from what we've been doing.”

Miss Opal’s petition went from 80,000 signatures at the end of May to more than 800,000 by Juneteenth, and she delivered 1.5 million signatures to congress last fall.

“It’s not just one little old lady in tennis shoes,” jokes Lee.

“Juneteenth took a boom, just blew up,” said Sims.

A bipartisan bill to make Juneteenth a national holiday failed to move forward by unanimous consent after Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin voted against it.

“This is an educational opportunity for our country,” Sims said. “Remembering it allows you to make sure it doesn't happen again.”

To Opal, Juneteenth isn’t about happened on the day in 1865 or even 1939. It matters because of what it represents.

“Opal makes the point over and over that it's a holiday for everyone,” Kennedy said. “It's the day that everyone gained freedom.”

“Now you wake up a whole generation that didn’t know anything about it,” Sims said. “That's why Juneteenth is really important, because it's about knowledge and a choice because knowledge is power.”

She sees it’s a yearly reminder for everyone to come together.

“I’d scream it from the housetops that unity is freedom,” said Lee.

It’s the most important lesson from the educator who has hasn’t stopped trying to teach.

“People have been taught to hate,” Lee said. “And if people have been taught to hate, they can be taught to love.”