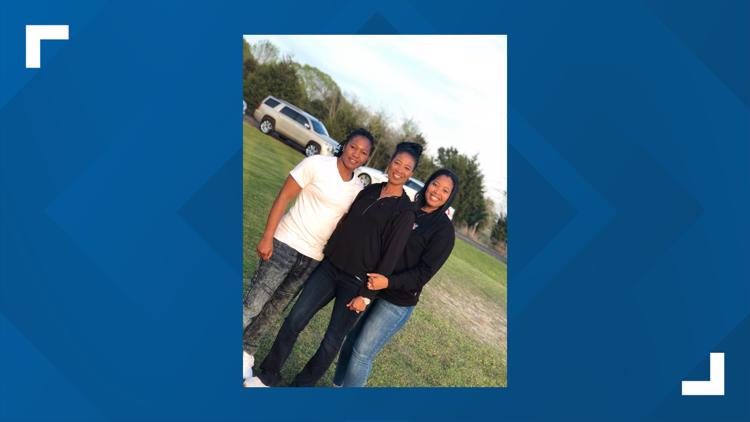

DALLAS — The laughter comes easy when you’re friends for life.

“When we met, it was just like we had known each other -- forever,” Brittany Barnett said.

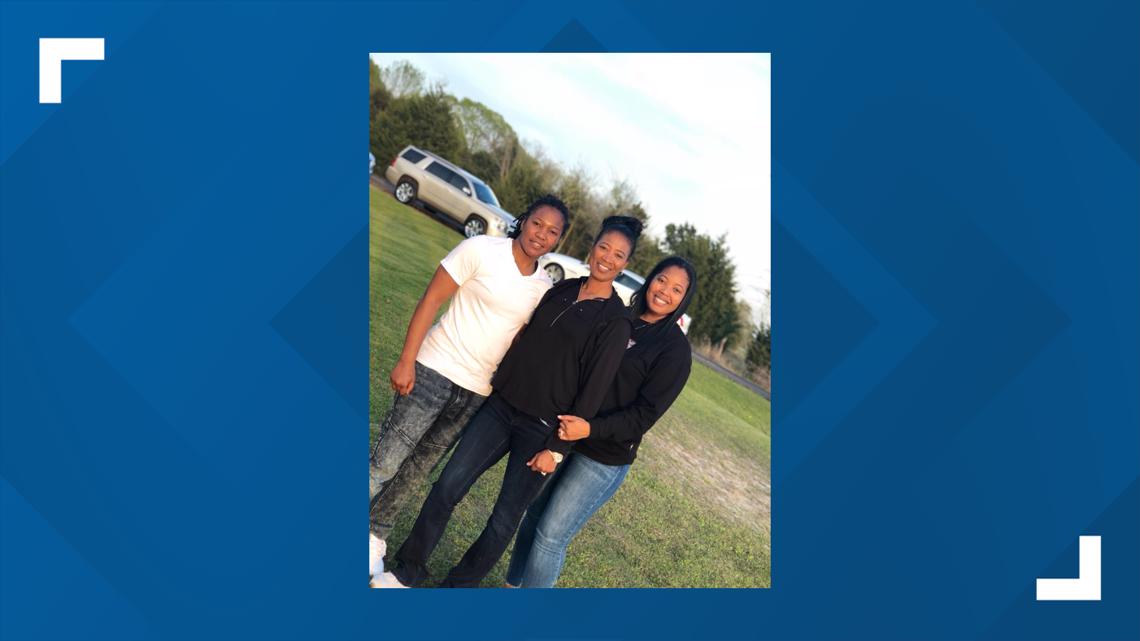

Her friend, Sharanda Jones, agrees, smiling as they enjoy each other’s company sitting on a bench in a downtown park.

“To be sitting out here, breathing, this nice fresh air, this is like, amazing,” Sharanda said.

Theirs is a friendship born out of Brittany's fight to free Sharanda, who was serving a life sentence when they met 12 years ago.

Back then, Brittany was a 24-year-old law student at Southern Methodist University taking a critical race theory class. While working on a paper for the class, a Google search led Brittany to a YouTube video about Sharanda.

Sharanda was a first-time, non-violent drug offender who had been sentenced to life in prison without parole on a drug conspiracy charge.

Her story tugged at Brittany’s heart and her sense of justice.

“Sharanda was serving the same amount of time in prison as the Unabomber,” Brittany said.

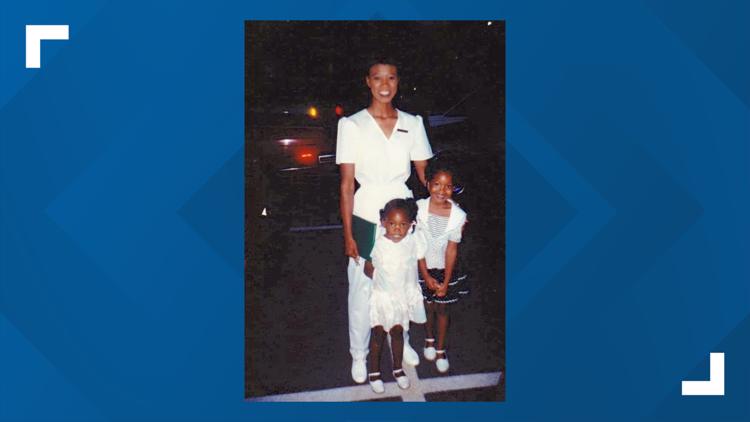

Sharanda grew up in poverty in Terrell, one of five children. An auto accident left her mother paralyzed when Sharanda was just 3 years old.

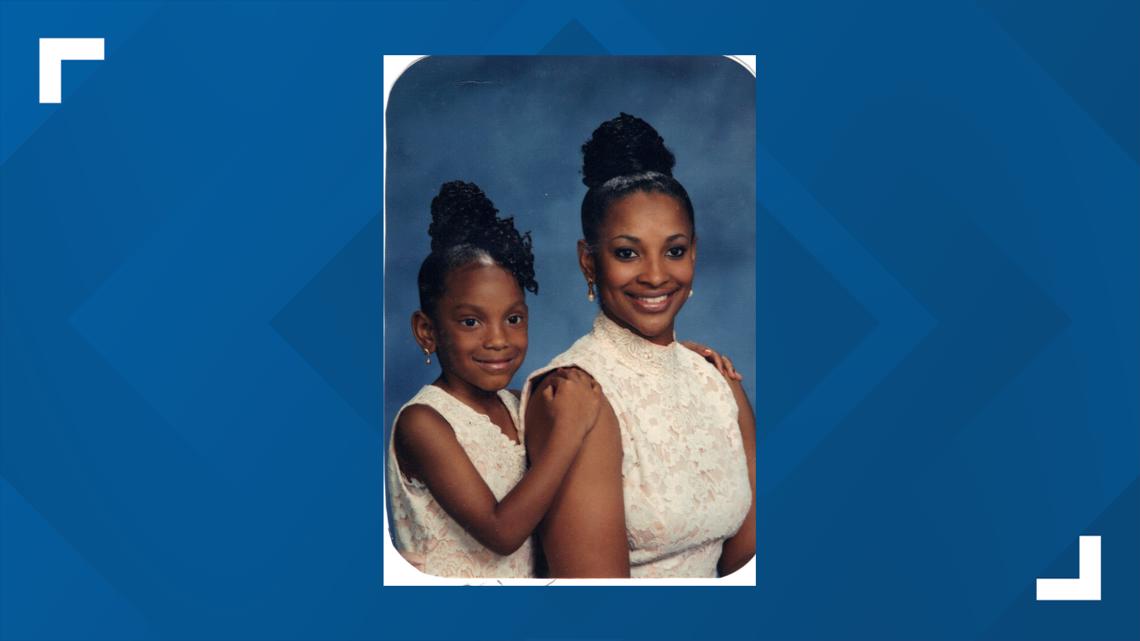

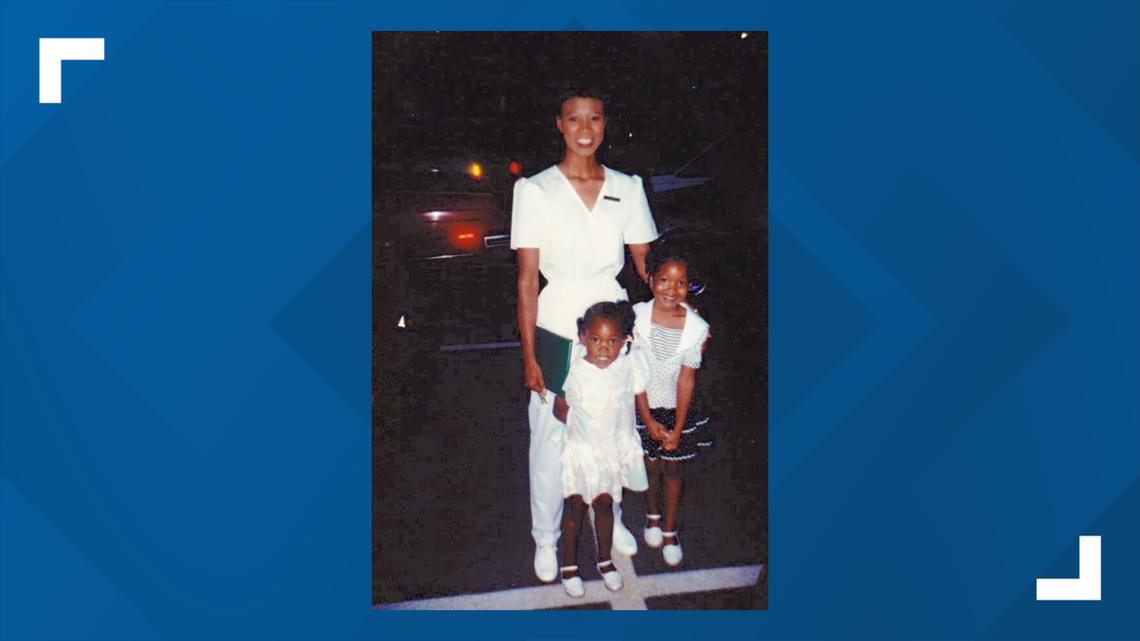

She graduated high school and opened a hair salon and a restaurant in Dallas. She was a single mother of an 8-year-old girl.

Money was tight. To make a little extra money, she’d made several trips from Houston to Dallas to buy cocaine from a drug supplier. She sold it to friends who were converting powder cocaine into crack cocaine to sell.

“I never dreamed that those three trips would lead me to a life sentence in prison,” Sharanda said.

Sharanda said prosecutors wanted her to take a plea deal and testify that a friend of hers, a police officer, had been involved. She said the police officer friend had nothing to do with it and she wasn’t going to lie – even in exchange for less prison time.

She opted to go to trial.

But what she didn’t know was that federal prosecutors win nearly every case, and there would be a huge price to pay for exercising her constitutional right.

At trial, prosecutors sought to portray her as a drug kingpin, although there was no physical evidence to back up the claim.

Sharanda testified on her own behalf. Several people – including Sharanda’s drug supplier – testified against her as part of plea deals to get reduced sentences.

“Sharanda worked essentially as a drug mule taking drugs on the interstate from one drug supplier to another on a handful of occasions, receiving $1,000 here and there for her efforts,” Brittany said. “The drug supplier in the case who admitted to trafficking hundreds of kilograms of powder cocaine, received less time than Sharanda Jones.”

Jurors found Sharanda not guilty on six counts, but guilty on the seventh.

On the morning of her sentencing, Sharanda worked at her restaurant, situated on Lamar Street next to what would be later become Dallas police headquarters.

“I got dressed for court thinking that after the lunch hour, after I finished court, I would come back and help clean up and prep for the following day,” she said, standing in front of what used to be her restaurant. “So I left here for lunch and never returned.”

A life sentence, a draconian law

Sentencing in federal court is based on a point system. The judge in Sharanda’s case calculated the amount of drugs based on the word of those who testified against her.

Then he kept adding more points. Points were added on because she testified in her own defense at trial. The judge decided her testimony amounted to perjury. He gave her points for possessing a gun. Sharanda had a concealed weapons permit and there was no testimony to indicate she ever used it or engaged in violence.

In all, the points stacked up to a life sentence.

“I was basically very, very numb when he said life,” she said.

Sharanda had been sentenced under a draconian drug law enacted by Congress in 1986.

That Anti-Drug Abuse Act, signed into law by then-President Ronald Reagan, made the penalty for crack cocaine 100 times more harsh than the penalty for powder cocaine – a penalty disproportionately resulting in Black people being sent to prison for decades and often for life.

Later, an appeals court would conclude in upholding Sharanda’s conviction that evidence of her involvement in a “conspiracy to distribute (crack) cocaine is sufficient but only barely so.”

Sharanda’s brother, sister and her paralyzed mother also received lengthy prison sentences.

Behind bars, Sharanda did everything she could to remain positive and better herself. Initially sent to a federal prison in Florida, she managed to get transferred back to the Federal Medical Center Carswell, so that she could help care for her mother.

Though she was a model inmate, she had no chance of ever getting parole.

Driven by personal experience to help others

While Sharanda languished in prison, Brittany was growing up in rural east Texas.

“I wanted to be Claire Huxtable on The Cosby Show,” she told WFAA. “She was the only lawyer I knew, or thought I knew. You know, growing up in my small community, there were no lawyers. There were definitely no lawyers who looked like me, and so I wanted to be her.”

Brittany was surrounded by a loving family.

But there was heartbreak. She watched helplessly as her mother, a nurse, spiraled downward into crack cocaine addiction. She was just embarking on her career as an accountant at 22 when a judge sentenced her mother to prison for drug possession.

“My mom needed help,” Brittany said. “She needed rehabilitation, not punishment.”

Her mother was released from prison in 2008, the year that Brittany started law school.

Brittany could see herself in Sharanda’s story.

Her high school and college boyfriend had sold drugs. On occasion, she’d traveled with him to Dallas when he bought drugs. Years later, she would come to realize that she would have been charged under federal drug conspiracy laws.

“I had to fight for Sharonda Jones's life, as if it were my own because it was,” Brittany said.

After seeing Sharanda’s video, Brittany decided to send her a card. She told her she was a law student, knew next to nothing about criminal law, but was going to get her out of prison.

Sharanda had received many letters over the years from lawyers but they wanted big money she did not have. So, with nothing to lose and only freedom to gain, she agreed to a visit with Brittany.

“It wasn't like meeting a stranger,” Sharanda says. “During our first conversation, we was like family.”

For the first time, she felt real hope that someone could get her out and a belief that the young lawyer-in-training was that person.

Many, many more visits would follow as Brittany fought to free Sharanda.

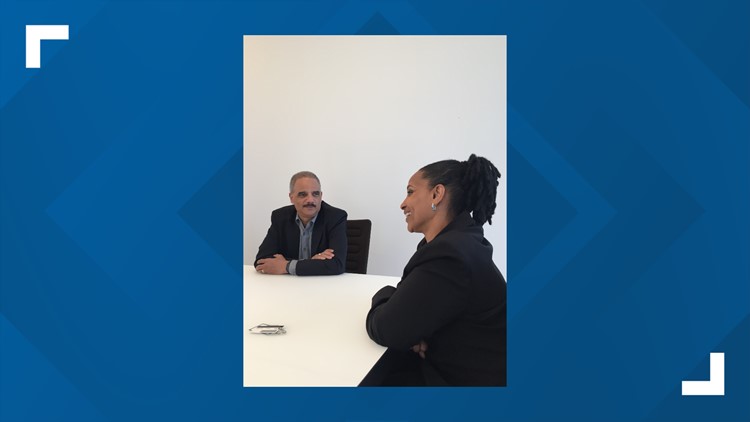

Taking a fight for freedom to the highest office

Over time, Brittany graduated law school and embarked on her career as a corporate attorney. She juggled the challenging demands of her day job and spent her evenings, nights and weekends working on Sharanda’s case.

She also began work on similar cases of others who had been incarcerated for life under those same drug laws.

Still, a miracle would be needed to get Sharanda out.

Congress had drastically reduced penalties for crack cocaine in 2010. Those changes were not retroactive, meaning they didn’t help people sentenced under the old laws.

So, people like Sharanda were trapped.

“You have people serving life sentences today under yesterday's drug laws, and for me, if the law is wrong today, it was wrong yesterday,” Brittany said.

Brittany Barnett and Sharanda Jones: 2 Texas women fight to help others find justice, freedom

Sharanda’s mother, paralyzed all those years earlier, died of a staph infection in 2012. Sharanda was not allowed to attend her funeral.

Britany eventually realized the only path to freedom was through the White House. She petitioned the president of the United States asking for clemency for Sharanda in November 2013.

More than two years later, in December 2015, President Barack Obama granted Sharanda clemency. Brittany’s six-year fight to free Sharanda had come to a close.

By the time of her release, she’d spent more than 16 years in prison.

“I was crying so hard,” Sharanda recalled. “It's like a story. It's a real movie story.”

Sharanda has been out now for five years.

She’s the doting grandmother of her 4-year-old granddaughter.

Brittany’s mother is doing well and works as a recovery nurse at a Dallas drug rehabilitation center.

Brittany left her job as a corporate attorney in 2016. She and Sharanda, along with another client who received clemency through Brittany’s efforts, have formed The Buried Alive Project. They offer pro bono legal representation to people serving life in prison due to what they consider outdated drug laws.

“I'm grateful that they've trusted me with their lives,” Brittany said, her voice breaking with emotion.

So far, she’s helped 11 people serving life sentences under those old drug laws to secure clemency. Most recently, two of them received clemency from outgoing President Donald Trump.

Life sentence transformed into life-long mission

There remains much to be done. There are more than 2,000 federal prisoners serving life for nonviolent drug offenses, according to the Sentencing Project.

Brittany detailed her life’s story and her journey to free Sharanda and others in a moving book entitled “A Knock at Midnight.”

As Brittany and Sharanda reminisced together recently on that park bench, they were reflective.

“We have more people to fight for,” Sharanda said, now 53.

“We do,” Brittany responded. “A lot of people.”

Dreams come big and small.

Sharanda’s restaurant dream remains alive.

She’s finishing renovating a food truck she bought and plans to call it “Fed Up” – a play on words reflecting on her own experience in federal prison.

Brittany has invested in the venture, and Sharanda plans to hire other formerly incarcerated individuals.

“I can't wait to say, ‘Can I take your order,’” she said with a laugh.

Sharanda is now living and loving life after almost serving life.