ARLINGTON, Texas — On the edge of the UT Arlington campus, inside a fence at Doug Russell Park, is a place most people don’t know exists.

“No, there’s a lot of people who don’t,” said historian Lydia Brosowsky. “Even students at UTA, some of them don’t know it’s here.”

Brosowsky stumbled upon it while writing her master’s thesis on the place. It’s a place known today as the Lost Cemetery of Infants.

About 100 years ago, dozens of unnamed children were buried in the cemetery, but what sounds haunting is actually quite heartening.

“This is all that’s left, the cemetery,” Brosowsky said.

Much of the land where the park sits today used to be The Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls. In other words, a home for women who society considered ‘outcasts.’

A preacher named JT Upchurch, and his wife, started Berachah to help those women gain life skills that would allow them to live a productive life.

Particularly, Upchurch and his wife sought to help homeless and unwed, single mothers. The women were provided housing, classes and training among the campuses many buildings.

“It just seemed like the girls had a decent chance to make it in life if they came here,” Brosowsky said.

And many women did make it, but not without tragedy.

Several women lost their babies either during birth, the Spanish flu or to other diseases, before they even had a chance to give their children a name.

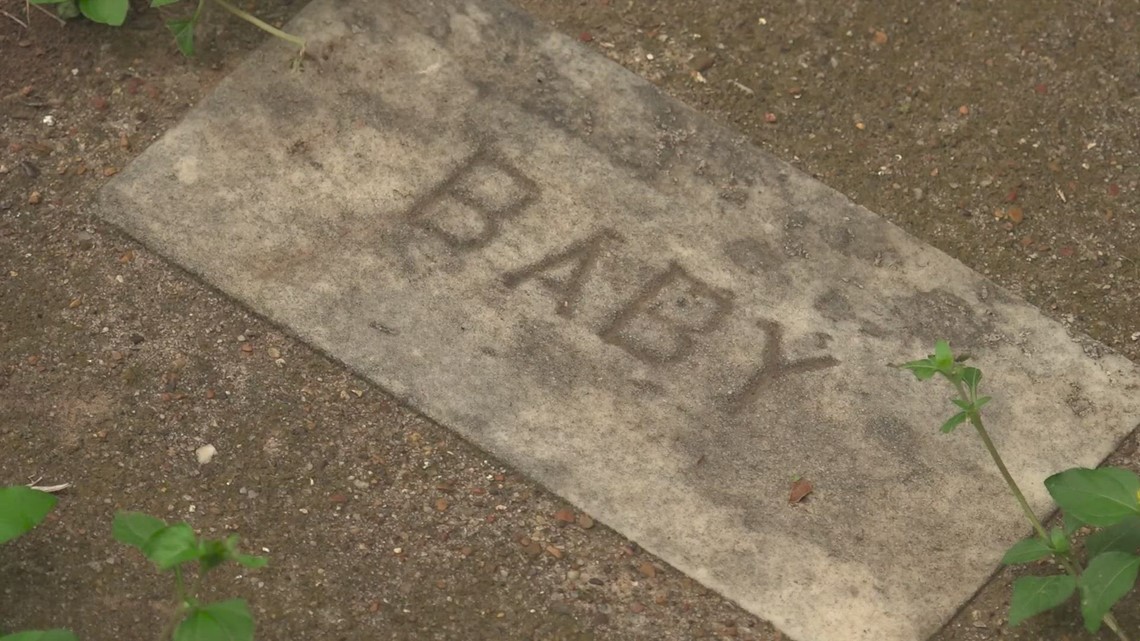

That’s why dozens of the nearly 80 graves are simply labeled “Infant,” with a number added, like “Infant No. 1,” to indicate how many children had died.

Deep in a wooded area of the park, it’s a cemetery thousands of college students unknowingly walk past every day.

Berachah Home closed in 1935 but today, visitors claim the spirits of those children still reside in the cemetery. Some people leave behind toys as proof.

“People will say that the toys move from one marker to the other,” Brosowsky said.

Others have claimed to hear children laughing, but Brosowsky says she’s never heard anyone who was scared.

“I feel nice when I come out here,” she said. “I feel comfort when I come out here.”

Maybe because, she says, it wasn’t a sad place. It was a place where many women found hope. Hope in a society that told them they didn’t belong, which is why this may be the friendliest fright in town.