ANCHORAGE, Alaska — The video portion of this story aired in two parts. To see part two, scroll down.

Alaska is a stunningly beautiful land of snow and ice.

It’s also one of the fastest-warming regions on earth.

My name is David Schechter. I’m the reporter/host of Verify Road Trip, and I recently went on an epic adventure to Alaska with one of our viewers, Justin Fain.

He's a 38-year-old roofing contractor and a staunch conservative. Justin rejects the mainstream scientific conclusion that the climate is changing and humans are to blame.

“I've thought all along it’s a natural occurrence,” Justin says. “I just don't believe it's something that we're causing or creating."

At the end of the Alaska trip, Justin answered three questions. Is the climate changing? Are humans to blame? And how urgent this is?

But before Alaska, Justin and I traveled across Texas.

We learned from top university scientists that in a matter of decades we've spiked our atmosphere with carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, which is causing the average temperature on the earth to rise.

“My main takeaway from the first part of the trip is everyone is against me,” Justin said and then laughed, playfully. “They weren't against me. But they had different opinions than me,” he says.

So, with the first half of our travels complete, the jury was still out for Justin.

THE ALASKA JOURNEY BEGINS: HIKING TO A GLACIER

We're meeting up with by Dr. Brian Brettschneider. He's a climatologist with the University Alaska Fairbanks. Brian wants us to see a glacier, and that means we're going on a hike on the Portage Pass Trail.

“This is a route that people have been taking for thousands of years,” Brian says.

It’s one mile uphill, in the rain. And while Brian seems to be doing just fine, for us it’s much harder.

“Wow, that was a hike,” Justin says when we make it to the top of the pass.

Below us, is Portage Glacier flowing into a silvery-grey lake.

“By every metric, by every measure, our temperatures are significantly warmer here than they have been decades ago,” Brian tells us.

This report from 13 United States government agencies, including NASA, show since the '70s the earth has warmed 1.5 degrees F. But Alaska has warmed 3.5 degrees.

As a result, many of Alaska's glaciers, like Portage Glacier, are melting.

“At one point, in the early 1900s, it filled up this entire valley. There was no lake,” Brian tells Justin.

“What do you think about that?” I ask Justin.

“Pretty wild. It's not here anymore,” Justin says.

“Where we're sitting right now would have been under 500 to 700 feet of ice,” Brian adds.

“So how do we know that that's just not what glaciers do?” Justin asks Brian. “They don't just go away and come back? How long have we been studying them to know that's what they do?”

“Great question. Glaciers are dynamic. They surge. They retreat. They've done that for long before people were here. But it's the rate,” Brian says.

The rate whereas a glacier might have receded over hundreds or thousands of years, now it's decades.

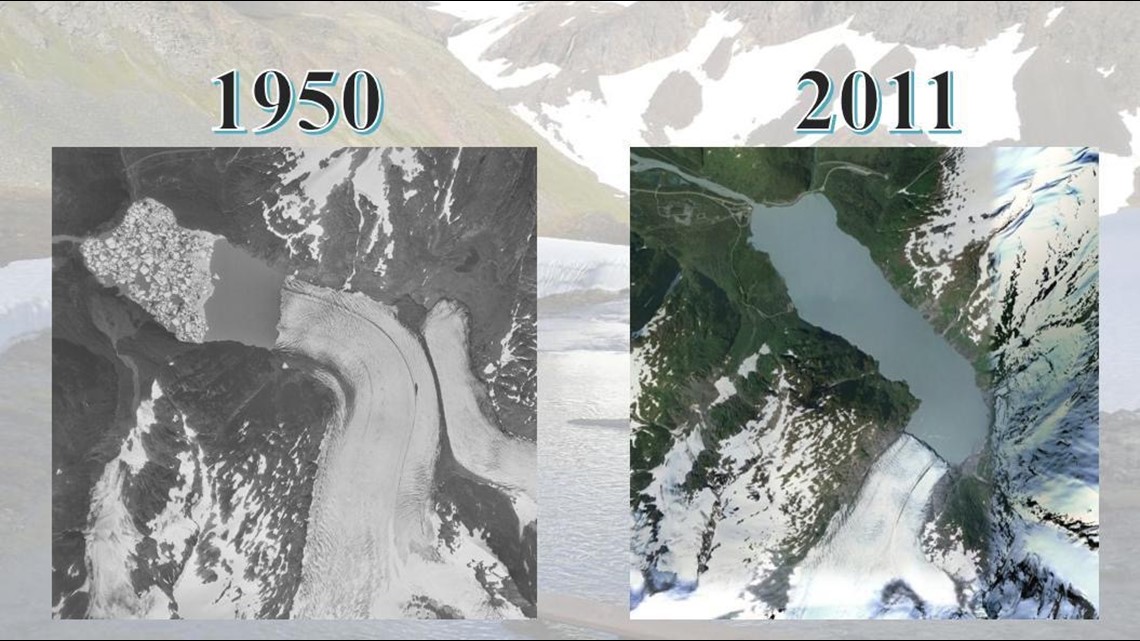

To understand that, it’s helpful to look at a picture from Portage Glacier from 2011 and compare it to 1950. The glacier used to snake across the lake in the valley. Now, the glacier is almost out of the water.

This report, in the journal Climate Dynamics, projects many glaciers around the world will lose half their ice volume by 2050. Glaciers are an important source of drinking water in nearby Anchorage and around the world.

“What do the glaciers tell us about climate change?” I ask Brian.

“Particularly in southern Alaska, the glaciers are right on the edge,” he says.

“They get tremendous amounts of snow and precipitation and they're just barely below freezing. Warm things up, even just a little bit, you turn a tremendous amount of that snow into rain. Not only does that rain not add to the snow pack and ice volume. It also melts ice when the rain falls on it,” Brian explains.

“So, it's raining instead of snowing?” I follow up.

“Much of the year it's now raining instead of snowing,” Brian says.

As our time with Brian wraps up, what’s Justin thinking?

“Might be something to be worried about,” Justin says.

WADING INTO A SALMON STREAM

Dr. Doug Causey is a biologist with the University of Alaska Anchorage. We’re walking the Trail of Blue Ice to a salmon stream in the Chugach National Forest.

“Full disclosure, I think our elevational change is like four feet,” Doug teases us after learning about our tough hike on the Portage Pass.

Doug studies the ecology of this area, including the salmon that spawn here just before they die.

“So, is this salmon right here?” Justin asks as we begin seeing fish in the river.

“Yes, this is Coho salmon,” Doug says.

To show us how warming temperatures affect living things, Doug wants to take us into the stream to take some measurements. But Justin forgot his rain boots in the car and has to walk through the water without them.

“Getting into the water I knew was going to be cold. I didn’t know how extremely cold it might be,” Justin says.

With Justin’s help, Doug measures the water temperature of the stream.

“Right now, it’s four degrees warmer than it was last year,” Doug says.

“That's one data point,” I say.

“One data point. We would want to continue to collect,” Doug says.

But scientists in Alaska have years of measurements. They've concluded the stream water is getting warmer (page 5); with last summer being particularly warm. Chinook and Coho populations are on a gradual decline (page 25).

As we see dead salmon in the stream Doug tells us that’s normal. This is where they go to die. Doug's saying, what's not normal is how few salmon we're seeing.

“We're seeing that the water temperature in streams is increasing,” Doug says.

“Change of one degree is a big difference?” Justin asks.

“Yes,” he says. “For a fish, like the salmon, what to us would be a very small change turns out to be a very important, big change for them. Even that small amount, whether it's two or five degrees, they can't go through their reproductive cycle,” Doug adds.

“When that happens, you're going to start looking for a reason and the reason you concluded to is the climate change?” Justin asks.

“Primarily, yes,” Doug says. “But salmon don't live by themselves in an aquarium. They're part of an ecosystem. And if they're being affected by climate change, the ecosystem is,” he finishes.

As we leave the stream, Justin checks in with a few observations.

“He wants the fish to come back. He wants the birds to be able to eat,” Justin says. “It's starting to concern me. Yes, very concerning."

PERMAFROST

Mark Clark is a retired soil scientist with the United States Department of Agriculture. He studies permafrost. He’s holding a shovel and telling us he likes to dig holes.

“This is a high-tech piece of equipment that soil scientists use. You've heard of GPS. This is our GPS. It's called a ground-penetrating shovel."

"High tech,” he jokes.

Permafrost is earth and ice that stays frozen, even in the summer. It stays frozen under a spongy, active layer of insulation that can freeze and thaw a little each year. Locked away in the permafrost is a massive amount of carbon dioxide.

“In interior Alaska, some of that carbon is 40,000 years old. This old carbon, this 40,000-year-old carbon, is starting to become exposed. That active layer that thaws every summer is now extending further and further down, in some places it is disappearing,” Mark says.

Justin and I have already learned that carbon dioxide is the likely cause of increasing global temperatures.

Mark is telling us, 50% of the carbon on land is locked underground in the arctic and sub-arctic. As the permafrost continues to thaw, more and more carbon will come out.

“How much is that? It's equivalent to the amount of CO2 that's currently in the air. On the planet,” Mark says. “It's like a hair trigger and it's just ready to be pulled."

“That blows me away,” Justin says.

“That's a lot of carbon, isn't it,” Mark says.

What is Justin thinking about what he learned from Mark?

“Permafrost under here is starting to melt, in quite a few of these places, due to the higher temperature. It’s pretty crazy. Pretty concerning as well,” Justin says.

CONCLUSION

When we started, Justin didn't believe in climate change, at all.

Throughout our journey, we've learned it's extremely likely that a rapid spike in carbon is the cause of climate change. Unlike in Texas, the effects are more obvious to the eye. The permafrost is thawing, the fish and wildlife are stressed and the glaciers are receding.

Now it’s time to wrap it up.

“We have three questions, right?" I say to Justin. “Is the climate changing in an abnormal way?” I ask.

“I would say so, yeah,” Justin says.

“Do you think humans are causing it?” I ask.

“If not causing it, contributing in a major way,” he answers.

“Zero to 10, how urgent is this problem for you?” I ask.

“I would say back at the beginning, this problem was a two. I would say I'm up to a six or seven now,” Justin says.

“That's a big change. Can you make a connection between being here and seeing it in Alaska and what might happen in Texas one day?"

“If what's happening here does start happening in Texas one day it's going to be an issue,” Justin says.

So, for Justin, the impact wasn't learning about the science. Instead, it was seeing the changes, which Justin concluded the climate is changing.

Don't take my word for it. Take his.

Got something you’d like verified? Send an email to david@verifytv.com